Projects

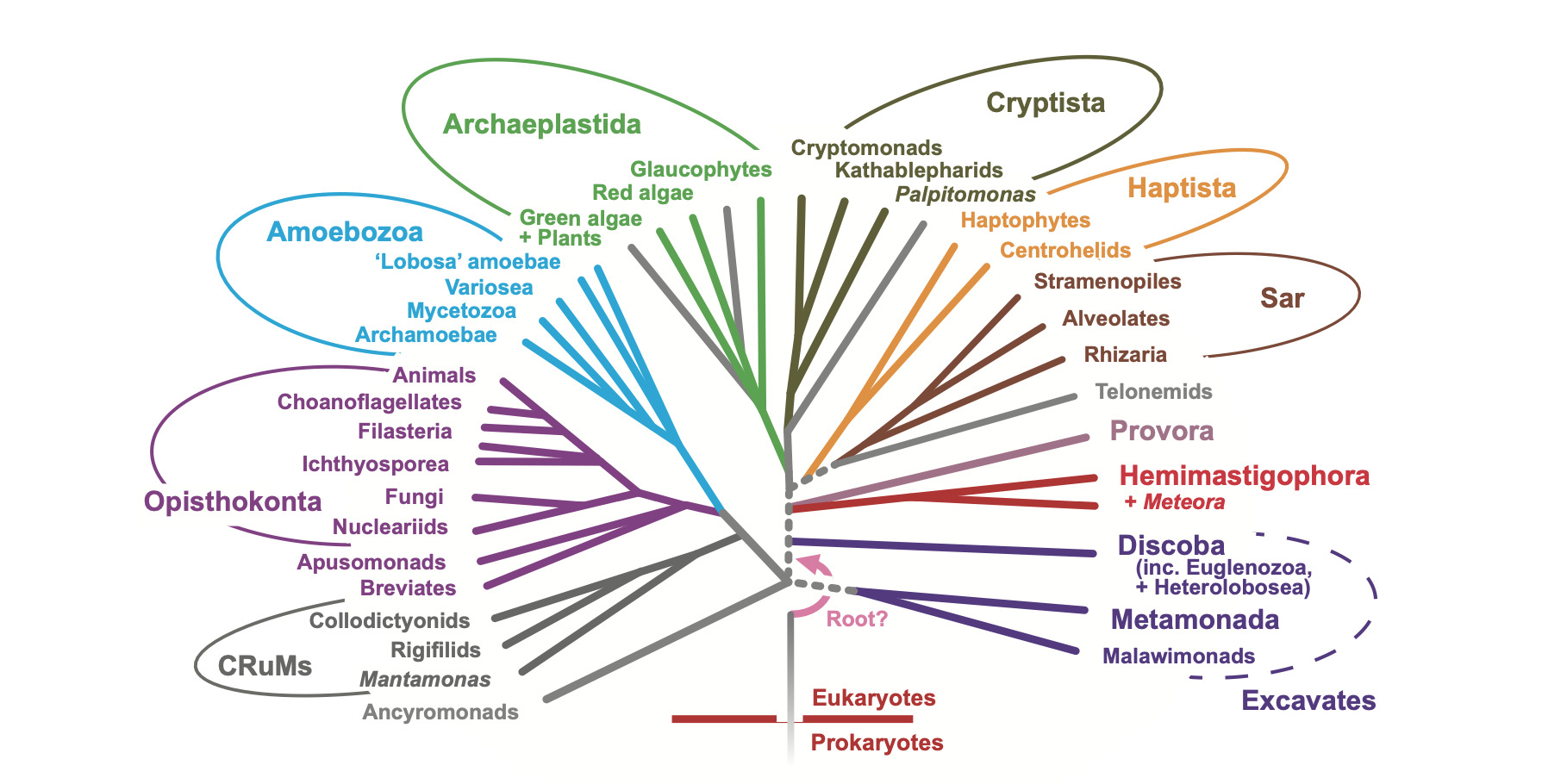

We study the biodiversity and evolution of unicellular eukaryotes (~protists), especially free-living protozoa. Free-living protozoa are of profound evolutionary importance; at the level of ‘major lineages’ they are more diverse than all other kinds of eukaryotes put together (i.e. animals, plants, fungi, algae and obligate parasites). In fact, all these other kinds of eukaryotes descend directly or indirectly from free-living protozoan ancestors. Free-living protozoa are also of huge ecological significance, representing the major predators of bacteria and other micro-organisms in many ecosystems.

Most of our projects examine poorly-studied protozoa that are especially important for inferring the evolutionary history of eukaryotic life to piece together what the last common eukaryotic ancestor (LECA) was. We also study protists that inhabit extraordinary environments and have undergone major adaptive change relative to ‘typical’ eukaryote cells. We also examine the diversity of ecologically important protozoa from sediments, and symbiotic or parasitic associations between protozoa and other marine organisms.

- Phylogeny and evolution of eukaryotic life

- Evolution of excavates

- Free-living kinetoplastids

- Biodiversity of phagotrophic euglenids

- (Extremely) Halophilic and alkaliphilic protozoa

- Other/ Past projects

Phylogeny and evolution of eukaryotic life

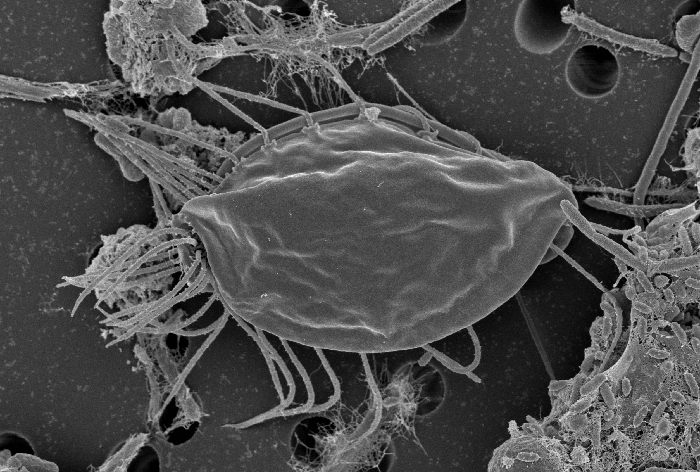

Scanning Electron Microscopy image of Hemimastix kukwesjijk. Photo by Yana Eglit.

Certain groups of (mostly) free-living protozoa occupy important deep-branching positions on the tree of eukaryotic life. These include the ‘typical excavates’ (see below) as well as various poorly understood flagellates such as ancyromonads, apusomonads, breviates and Mantamonas.

In collaboration with several other research groups (inc. the Roger lab at Dalhousie University, Matt Brown at Mississippi State, and Yuji Inagaki’s group at Tsukuba) we use phylogenomic approaches to infer the tree of eukaryotes including these important overlooked taxa. We have shown that breviates and apusomonads are together closely related to the group containing both animals and fungi (opisthokonts), forming the group now called Obazoa (Brown et al. 2013). We have also identified a new ‘supergroup’ on the eukaryote tree, ‘CRuMs’, that is composed of various free-living protozoa (Brown et al. 2018).

We have also characterised the cytoskeletons of these organisms, primarily using serial transmission electron microscopy (e.g. Heiss et al., 2011, 2013a, 2013b; Eglit et al. in prep.). These studies show that certain distantly related living eukaryotes share several homologous cytoskeletal elements. This implies that all living eukaryotes descend from a common ancestor with a complex flagellar apparatus cytoskeleton, and remarkably, that we will are able to reconstruct much of this cytoskeleton, despite the passage of more than a billion years.

In ongoing research, we are characterising several new or ‘lost’ free-living protozoa that likely represent additional major lineages on the eukaryote tree of life. Our study of the Hemimastigophora, employed single-cell transcriptomic methods to allow us to conduct phylogenomic analyses (Lax, Eglit, Eme et al. 2018, Nature 564: 410–4). Hemimastigophora proves to represent (another) new supergroup for which we had no molecular data for at all, and it represents a crucial taxon to consider for understanding the properties of the last eukaryote common ancestor, the location of the root of the eukaryote tree, and many other questions. Recently we discovered that the bizarre arm-waving protist Meteora is a close relative of Hemimastigophora, despite having almost nothing in common in cell architecture (Eglit, Shiratori et al. 2024, Current Biology 34: 451-9). This cultivation, phylogenomics, mitogenomics and TEM study was a collaboration with Ken Ishida's group at Tsukuba and the Roger lab at Dalhousie.

Excavate evolution and function (and anaerobes)

Several groups of heterotrophic flagellates have a distinctive type of feeding groove. Some time ago, we characterised these groups (and their immediate relatives) as the ‘excavates’, and argued for their common ancestry based on the structural similarity of the groove cytoskeleton in typical forms (see Simpson, 2003 for a review; also Heiss, Kolisko et al. 2018). Ourselves and collaborators have now extensively studied the difficult-to-resolve evolutionary relationships amongst excavates. Multigene phylogenetic and phylogenomic analyses do identify three robust clades of excavates; Discoba, Metamonada and Malawimonadida (e.g. Simpson et al 2006, 2008; Hampl et al., 2009). Yet recent phylogenomic analyses of distinct datasets (e.g. Heiss, Kolisko et al., 2018; Eglit, Shiratori et al. 2024; Williamson et al. 2025, amongst several) place malawimonads closer to Opisthokonta (animals, fungi etc), Amoebozoa and CRuMs than to Discoba. Metamonads remain challenging to place; we infer that they are closely related to malawimonads, and not Discoba, based on morphological and careful phylogenomic analyses (Heiss, Kolisko et al., 2018). Several analyses that include prokaryotic outgroups (e.g. Williamson et al. 2025) place the root of eukaryotes between malawimonads and Discoba. If so, either the typical excavate morphology is an extreme case of convergent evolution, or the last common ancestor of living eukaryotes (LECA) closely resembled living typical excavates, a remarkably specific statement about the deep evolutionary history of complex life on Earth.

This potentially key evolutionary importance of typical excavates has inspired a highly productive collaboration with Thomas Kiorboe’s group at the Danish Technical University, studying their comparative functional ecology and physics. Using examples from all three excavate groups, this gives the first detailed explanation of the function of the feeding groove, and why typical excavates have a vane or vanes on the posterior flagellum - the vane and groove seem to provide an energetically efficient way of generating a feeding current, but only in combination (Suzuki-Tellier et al. 2024a). We also documented a ‘new’ feature shared by example typical excavates – a wave that passes down the groove and helps complete phagocytosis of prey at its posterior end (Suzuki -Tellier et al. 2024b). Ourselves, the Kiorboe group, and the lab of Kirsty Wan (Exeter, UK) are now undertaking an HFSP-funded project to further examine feeding grooves in excavates and in groove bearing flagellates from other groups such as colponemids and nebulomonads, to relate structural similarities and differences to their functional and fluid-physics properties. Some ground-work for this was laid by our cultivating and describing new colponemid genera (Gigeroff et al. 2023), and the mysterious shallow-grooved flagellate Kaonashia that proves to be a stramenopile (Weston et al. 2024).

Metamonads are all anaerobes that have highly modified mitochondria, and include the well-known parasites Giardia (a diplomonad) and Trichomonas, as well as the commensalic/symbiotic oxymonads. It has long been known that there are free-living metamonads as well, but these are badly understudied. A long-running project of the lab is to isolate and characterise new free-living anaerobes, especially metamonads, such as Carpediemonas-like organisms and trimastigids (Kolisko et al., 2010, Park et al., 2009, 2010; Zhang et al., 2015). Carpediemonas-like organisms prove to be a highly diverse paraphyletic group that gave rise to diplomonads (Takishita et al., 2012), while trimastigids similarly gave rise to oxymonads (Zhang et al., 2015). Recently, PhD student Yana Eglit discovered the skoliomonads, and characterised several isolates (Eglit et al. 2024). Skoliomonads together with barthelonids (which she also helped culture and characterise for the first time - Yazaki et al. 2020) turn out to be a new deep branch within metamonads (BaSks - Williams et al. 2024). We also assist in collaborations, primarily with the Roger Lab at Dalhousie University, that trace the evolutionary modifications of the mitochondrion-related organelles and anaerobic biochemistry across metamonads using taxon-rich comparative transcriptomic and genomic datasets (Leger et al. 2017; Williams et al. 2024). In fact, Skoliomonas litria seems to be just the second eukaryote, and first free-living form, that is a strong candidate to completely lack a mitochondrial organelle (Williams et al. 2024).

Free-living kinetoplastids

Free-living kinetoplastids form the bulk of all kinetoplastid diversity yet remain relatively understudied compared to their parasitic counterparts. Nestled in the excavate supergroup Discoba, yet lacking the characteristic excavate groove, the position of kinetoplastids is well known, yet key parts of their internal phylogeny is unclear. In collaboration with Daryna Zavadska and Dr. Daniel Richter we are trying to resolve the deep phylogeny of kinetoplastids, including determining the root position for the largest subgroup, metakinetoplastids.

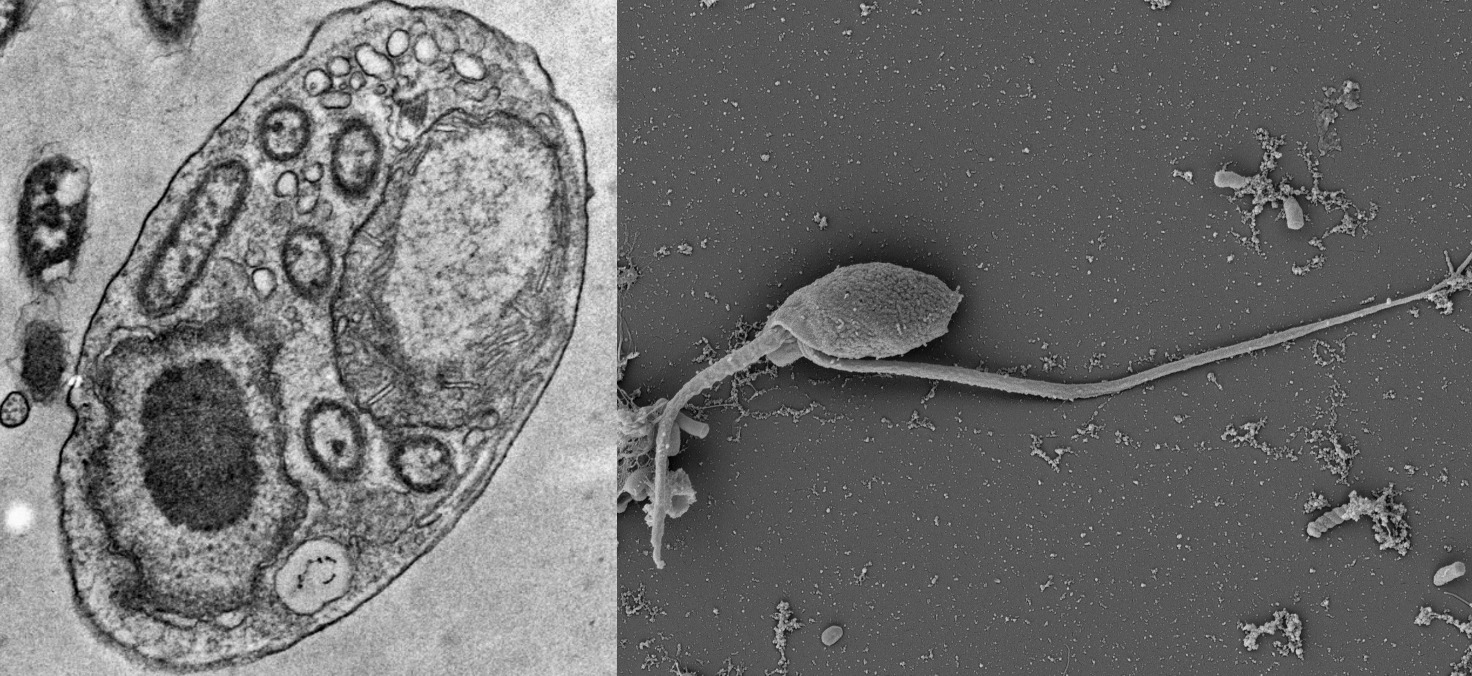

The genus Allobodo was originally described in our lab with one member, Allobodo chlorophagus (Goodwin et al., 2018). It ‘infects’ Codium fragile, a green alga, as either a parasite or nectrotroph and is found along the Atlantic coast of the USA and Canada. Allobodo also turns out to represent a new family-level taxon within metakinetoplastids, Allobodonidae. The second described member, Allobodo yubaba , cultivated recently by Daryna Zavadska, is free-living.

We have recently described a second genus of Allobodonidae, Novijibodo containing one member, Novijibodo darinka, a free-living alkaliphile that surprisingly harbours a Gram-negative bacterial endosymbiont (Packer et al., 2025). This availability of cultures covering the diversity of Allobodonidae will be valuable in resolving metakinetoplastid phylogeny using phylogenomics.

Biodiversity of phagotrophic euglenids

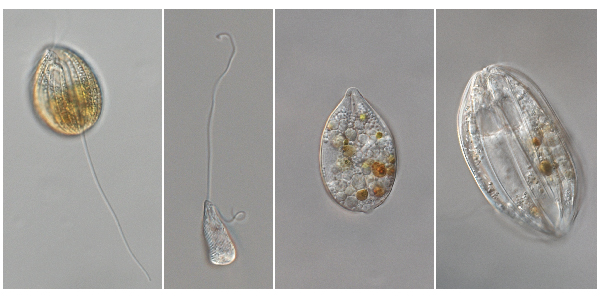

The major taxon Euglenida contains organisms with a broad range of morphological appearances and various nutritional modes including phagotrophy, osmotrophy, phototrophy and mixotrophy. Phagotrophic euglenids represent the ancestral form that gave rise to all other types (e.g. the phototrophic forms descend from a secondary endosymbiosis involving a phagotrophic euglenid and a green alga), and they are also important micropredators in sediments. Few phagotrophic euglenids have been cultured, however, and the whole assemblage is thus understudied. Current taxonomy is based on a variety of morphological features, but as molecular data are collected, the misleading nature of most of these morphological characters has become obvious.

We have characterised phylogenetically important phagotrophic euglenids with collaborator Won Je Lee, of Kyungnam University, South Korea (Lee and Simpson, 2014a,b; Lee et al. in prep.). We have also established workflows to isolate single phagotrophic euglenid cells from environmental samples, identify them with high-quality light microscopy and sequence their SSU rRNA genes (Lax & Simpson, 2013, 2020; Lax et al. 2019). This approach promises to rapidly capture much more of the taxonomic diversity of phagotrophs than by culturing alone. We have addressed several taxonomic, phylogenetic and evolutionary issues, including identifying which phagotrophic euglenids are most closely related to the osmotrophs, and demonstrating the non-monophyly of several genera, as well as numerous proposed higher taxa. This major expansion of the database of identified euglenids with molecular profiles will also improve our ability to identify euglenids in environmental sequencing surveys, where they are suspected to be badly under-detected.

We have also extended this work to obtain multigene profiles for photodocumented cells using single-cell transcriptomics (Lax et al. 2021). This approach will enable the estimation of multigene phylogenies to get a clearer picture of the phylogenetic relationships among euglenids, and their deep-level evolution.

Examples of phagotrophic euglenids. From left to right: Anisonema acinus, Heteronema sp., Notosolenus ostium (without flagella), Ploeotia cf. vitrea (without flagella). Photos by Gordon Lax.

(Extremely) Halophilic and alkaliphilic protozoa

Microbiology textbooks present very hypersaline habitats (>25% salt) as being exclusively inhabited by prokaryotes, mostly Haloarchaea, and the alga Dunaliella. In reality, there many heterotrophic protozoa that have been reported from extremely hypersaline habitats—at least 30 morphospecies by a conservative estimate (Park et al., 2009). These include ciliates, amoebae, and several groups of flagellates, some of which have unknown affinities within eukaryotes.

We have characterised numerous cultures of (borderline) extremely halophilic protozoa using electron microscopy and/or molecular phylogenetics, including several new genera (Park et al., 2006, 2009; Barkhouse et al. 2025). Some of this work was completed in collaboration with Prof. Byung Cheol Cho of Seoul National University, and/or former postdoc Jong Soo Park. Our research makes clear that obligate halophiles (organisms requiring salinities above seawater for growth) evolved many times among protozoan eukaryotes, for example, three times independently in the taxon Heterolobosea alone (Park et al., 2007, 2009, Park and Simpson, 2011, 2015; see review by Harding & Simpson, 2018). Almost all the obligate halophiles that we have cultured are distinct at the genus level from marine taxa, although we have also identified two lineages that apparently secondarily reverted to halotolerance (Harding et al., 2013; Kirby et al., 2015).

In collaboration with Andrew Roger's group at Dalhousie University we have used comparative transcriptomic analyses and genomic data to examine adaptations to halophily in representative halophilic protozoa (Harding et al. 2016, 2017). Halocafeteria (a stramenopile) showed differential expression under different salinities in numerous systems (e.g. stress responses, signal transduction systems, sterol metabolism). We also found an overrepresentation of differentially expressed eco-paralogs amongst recent gene duplicates, and two cases of relatively recent lateral gene transfer among the highly differentially expressed genes. Interestingly, Halocafeteria also turns out to possess a full pathway for synthesizing the ‘bacterial’ compatible solutes ectoine and hydroxyectoine.

Other/ Past projects

Recurrent mass mortalities of the green sea urchin Strongylocentrotus droebachiensis drive transitions between productive kelp beds and ‘barrens’ in shallow water on the Atlantic coast of Nova Scotia. The disease is caused by a facultative pathogen, the amoeba Paramoeba invadens. The source of outbreaks is mysterious, especially as the minimum thermal tolerance of cultured P. invadens is above the local winter minimum water temperature, which argues against local overwintering. In a collaboration with the lab of marine ecologist Bob Scheibling, we confirmed the distinctiveness of P. invadens using multiple gene markers (in Feehan et al., 2013), examined in detail its lower thermal threshold for growth (Buchwald et al. 2015), and have devised and tested PCR and qPCR methods for detecting P. invadens in tissue and environmental samples (Buchwald et al. 2018).

We also conducted a project on marine vampyrellids, specifically their biodiversity and feeding on microalgae (More et al. 2019, 2022; project run by former postdoc Sebastian Hess).